In 2019 François Chollet published the Abstraction and Reasoning challenge in the Kaggle platform with the goal to provide a benchmark to measure machine intelligence.

The Abstraction and Reasoning Corpus

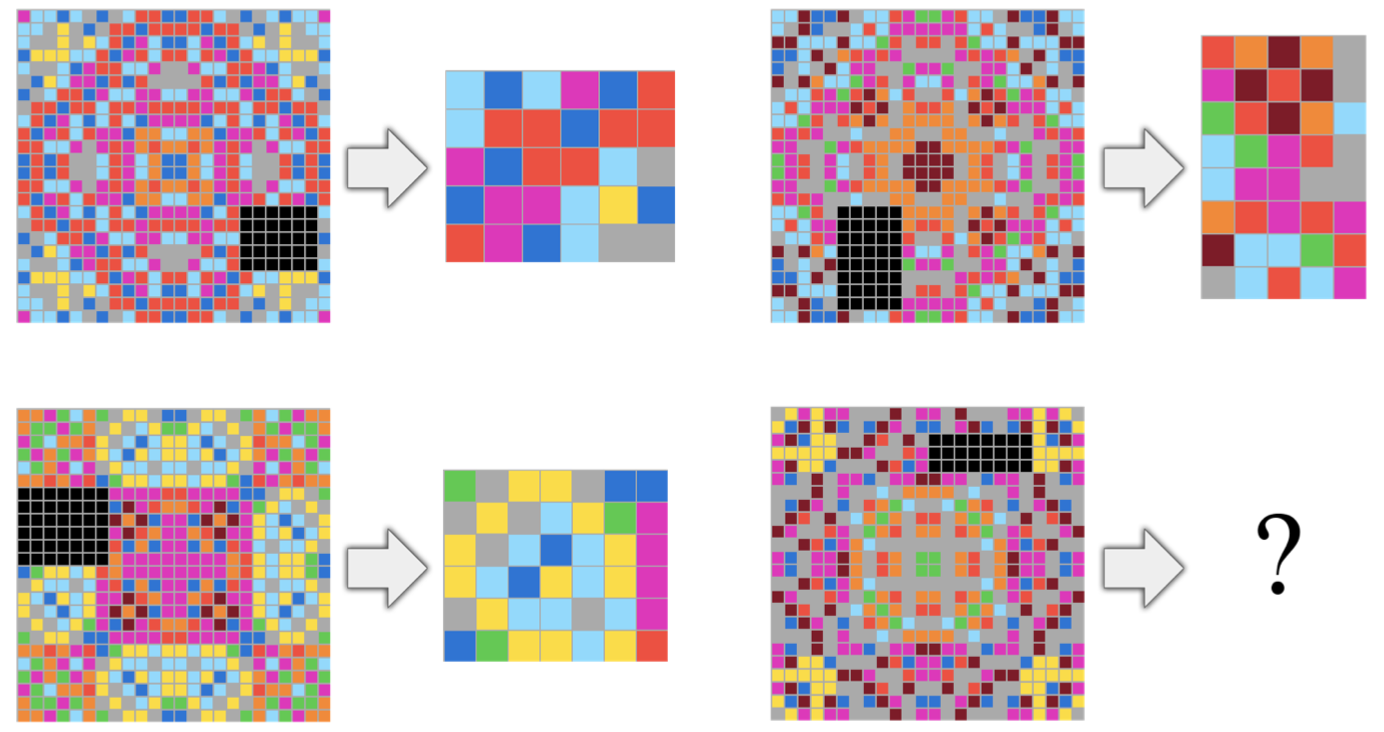

The Abstraction and Reasoning Corpus consists of a collection of tasks that are solvable by humans or by a machine or system. The task format is inspired by Raven’s progressive matrices, in which the test taker is required to identify the next image in the sequence.

Learning from a few examples

In order to prevent brute-force approaches where the system learns to exploit weaknesses in the data set, the ARC benchmark provides only a few examples for each task.

Chollet makes the case that the kind of intelligence we should be interested in, is the kind where the system can perform well, even after seeing only few examples of the task, similar to the way humans are able to solve this type of task.

A human test-taker does not need to train for solving a particular task, even when it has not seen it before, a system taking the ARC test still requires multiple non-intersecting data sets, one used during development, one to evaluate the system before the final test and the final data set, used to calculate the system’s score.

A system capable of achieving human-level performance in the ARC benchmark would necessarily be less intelligent than a human with the same score. This is because the human is expected to perform better with less exposure to the test format. It is assumed that a human should be able to obtain a score very close to 100% correct solutions. However, Chollet has said that he does not have the data to claim with certainty this is the case since it would require large-scale psychological studies.

Building systems with human-like intelligence

In order to build human-like AI systems, it’s possible to define some baseline knowledge and build it into our systems. The built-in knowledge is referred to as the system’s prior knowledge or priors for short. It includes intuitive notions about physics, e.g., how objects behave in the physical world, it also includes the notion of what agents are, and also how they behave.

What exactly the priors are is informed by theories about the human mind. One example of prior knowledge is Naïve Physics, it deals with the untrained human perception of physical phenomena, for example, the solidity and permanence of objects; another example is the ability to assign agency, that is, the ability to recognize intentions and goals in the behavior of agents.

Steering the evolution of intelligent systems

The choice of priors coincides with the types of knowledge that is expected from a newborn human. In humans, the priors were shaped by the process of evolution and they enable us to perform well on specific tasks. By specifying human priors in artificial systems, it is desired to nudge the development of those systems in directions that are useful to solve human-relevant tasks and also to speed up the acquisition of new skills.

Assigning human priors has another benefit, it opens the possibility to compare the intelligence between two different systems, something that remains an open problem to this day. Also, since the benchmark is solvable by humans, it would provide a more direct way to compare human and machine intelligence.

ARC is a new type of challenge in the Kaggle platform and it’s designed that way so that traditional Machine Learning techniques – which are data hungry – won’t work.

The suggestions from the challenge hosts are to attempt solving the tasks by hand and write down the programs that would solve them, then think how one could use principles of program synthesis and program search to find such programs. The next logical step is to find ways to rank and select programs which are likely to get a higher score.

Life experience a.k.a. acquired knowledge

Providing priors to the system only gives it a head start to acquire specific skills. One step further is to allow the system to learn and acquire new knowledge. This can be done via controlling the type of tasks a system is exposed to. Tasks can be designed such that they will help the system further improve the system’s performance in a particular direction.

It seems to me that the ARC data set is itself an exercise in Curriculum design, where the sequence of tasks the system is exposed to, is chosen in a way that will direct the system towards human-like intelligence. In the pessimistic case, it may only produce a system that’s good at taking ARC-type of tests and nothing else.

The designed curriculum limits the amount of examples the system is allowed to use for its learning before being able to solve new tasks, this is inline with the desired goal of producing systems that can generalize from few examples.

Focus on generalization

Humans are able to tackle more diverse tasks without any previous experience. We are able to create abstractions and then to manipulate those abstractions and apply them to new contexts, we can go from a single example to a general principle.

Contemporary approaches at measuring the performance of intelligent systems is to create task-specific benchmarks. In comparison, intelligence tests for humans measure the performance over a range of distinct tasks.

The measure of intelligence proposed by Chollet, accounts for a system’s performance over a set of tasks given it’s prior knowledge and experience. This means that it will rank higher systems that can solve more diverse tasks given only a few examples for each.

Evaluation

The ARC dataset is broken into stages, a set of tasks given in order to develop and tweak the algorithm to generate predictions. A different dataset to evaluate the performance of the algorithm before the final test stage.

For each task, the solution can generate up to 3 predictions and the score of a solution is calculated by averaging the error over the tasks, that is, by adding up the error for each individual task and dividing by the number of tasks. The error is 0 if the correct solution – ground truth – is contained in the 3 predictions generated by the system, the error is 1 otherwise.

A perfect score using this metric would be 0, meaning the system makes no mistakes. As of the writing of this post, the top solution has a score of 0.794, this means the system produces the incorrect solutions almost 80% of the time. Some improvements have been submitted based on existing solutions with top scores, however, they offer only marginal gains.

How close to AGI are we?

If we are to use Chollet’s ARC benchmark as a serious candidate to evaluate the intelligence of our systems, then we’re not very close to achieving human-like AGI. This assumes that every possible solution to ARC has been submitted and that the benchmark is actually useful to measure intelligence in humans and systems.

As of today I don’t know if Chollet has published his own best score for ARC but it would be interesting to know. All I could find was his answer to this very question:

That said, ARC is designed to be approachable right now, and I have a few approaches that yield decent results. 20% is a reasonable goal today, and can likely be beaten over the duration of the competition (I’d say it’s 50% likely to get beaten). The 2% progress we’ve seen in mere days on the leaderboard gives you a confirmation of that. Simultaneously, I think reaching human level will take many years. Kaggle discussion

The benchmark is young and much work is still to be done, some of the challenges are related to the ability from participants to find ways to trick the benchmark. In a way the publishing of the ARC challenge will help in identifying its limitations. There’s already plenty of talk in the Kaggle platform and elsewhere on how to achieve just that, that is for now out of my reach since they revolve around advanced concepts in the design of ML benchmarks. Fortunately this is also outside the scope of this post ;)